James N. Frey’s modern classic on crime writing scrutinised

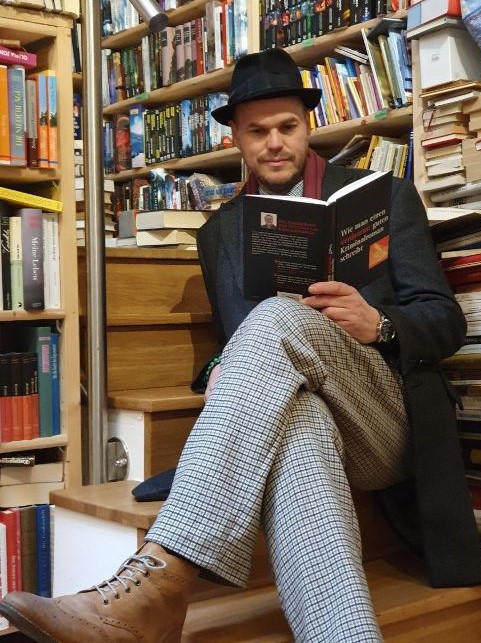

Review by Bernd Friedrich von Schon

| This post contains affiliate links {always indicated by a note in curly brackets}. If you buy something after clicking on one of these links, it will go into my coffee purse, because as an Amazon Associate I earn money from qualified purchases. Thank you very much! |

According to the blurb, James N. Frey’s book How to Write a Damn Good Mystery {Affiliate Link} offers a step-by-step guide from inspiration to finished manuscript for murder mysteries.

It is as gripping as it is amusing. Frey is regarded as a leading American teacher of creative writing, he has taught at the University of California, Berkeley, among others, and is the author of dramas, novels and non-fiction books on writing.

I have taken the liberty of taking a detective’s look at Frey’s tools of the trade when writing crime novels and savour the crème de la crème of his tricks here.

Why do you love murder mysteries?

Frey begins with the question of why we love crime novels of all things – after all, they deal with such unpleasant things as murder and manslaughter. With this question, he traces the functions that crime stories fulfil. This approach sounds promising, because: Knowing why we build a story and how, allows us practitioners to expect successful results. If we know what we are doing and why, this knowledge makes our actions conscious, effective and efficient because we are working towards clearly defined goals. This is why I also recommended identifying story functions in my article on innovation in the crime genre.

Frey’s answer to the question „Why do we love crime stories?“ is:

Because …

1. … our desire for someone to ensure justice in our dark world,

2. … the thrill of chasing criminals,

3. … the satisfaction of seeing wrongdoers face their deserved punishment,

4. … the feeling of understanding and reflecting on reality,

5. … the pleasurable exploration of the dark side of human nature and …

6. … the identification with the hero, so that we as readers feel „a little heroic“ ourselves.

Frey’s three Major Crime Fiction Genres

Although Frey is aiming to write bestselling crime novels, he nevertheless provides an insightful breakdown of the typical characteristics of different crime fiction subgenres. These can be recognised above all in the design of the protagonists. For example, the main character of a genre crime thriller is a bit „theatrical“ in the sense of exaggerated, larger than life, hereby a bit unreal, eccentric, sometimes even comic-like, therefore recognisable, but at the same time also a bit stereotypical. Detectives in mainstream crime fiction are often stuck in a moral dilemma, usually suffering from relationship problems; in this variation of the genre, the main focus is on the life the main character leads and how we act in a morally correct manner, often being painfully true to reality. Literary crime fiction protagonists lead a bleak life in a doomed civilisation.

I think the fact that Frey prioritises the creation of the characters in his book is excellent, especially for the murder mystery, because in the worse stories of the genre the puzzle structure often dominates the characters, they are far more often plot-driven than character-driven.

This is how you develop captivating characters, …

According to Frey, characters should be three-dimensional, i.e. they should be developed physically, socially and psychologically – i.e. in terms of their physical constitution (age, physique, ailments, tics, etc.), their social integration (family, friends, professional network) and their mental attitude (likes, dislikes, fears, hopes, values, inhibitions).

… how you create multifaceted villains, …

Frey describes the perpetrators as the secret authors of the crime novel. My favourite quote from Frey comes in connection with the development of villains:

»The unfortunate fact is that most of the time a crime writer is thinking about killing someone«

James N. Frey

Crime writers do this in order to create elaborate murder plans that set the wheels of crime dramaturgy in motion as the „plot behind the plot“. Precisely because the murder plan determines the structure of the background story, Frey considers the murderers to be the actual authors of the crime thriller. In this respect too, Frey’s method is similar to the one I taught students in my last crime fiction seminar.

According to Frey, perpetrators should be dominated by a ruling passion, it strengthens them if they are evil through and through, but skilfully conceal this – so that they can be exposed in the end. „Evil“ here means above all: selfish. Frey also classically recommends that criminals have been injured in the past (keyword: „backstory wound“). And that the tighter the noose tightens around them, the more they are ruled by fear. To commit the offence, they need – of course! – a motive, a means (of committing the crime) and the opportunity.

… likeable heroes, …

The heroic, investigative characters should also be drawn in three dimensions, also be driven by a ruling passion and have a special talent. They can also be a little quirky, outsiders on the edge of normality and have human flaws that make them likeable. In contrast to the selfish antagonistic character, they should be self-sacrificing and long for justice.

… and illustrious supporting characters

Since all the characters involved in a crime thriller become suspects, the secondary characters also need a plausible motive for the crime in addition to the obligatory three dimensions (physical – social – psychological).

All in all, the more cunning, clever and imaginative the dramatis personae are and act, the more enjoyable a crime thriller is. I can only agree with that.

How to bring your characters to life

Frey recommends writing a biography for each character before „plotting“ the story, with the most important key data of their life to date. In their character biography, you define the injury your character has suffered and develop how they became who they are in the three dimensions (physical – social – psychological). The main purpose of the biography is to motivate your characters, i.e. to explain where their dominant passion comes from and why they have made which decisions in the backstory – and will make them during the course of the plot.

How to make your characters speak authentically and individually

Your next tactic is to write a section of a diary from the point of view of each character, in their own style of speech. In this way, you approach the character from the inside out, so to speak, practise their way of speaking, their typical linguistic idiosyncrasies and develop their unmistakable voice.

I consider character biographies and diary ego narratives to be valuable preliminary work that allows you to orchestrate the characters with outrageous ease and create vivid contrasts between the characters. Moreover, they liquefy the later writing process because you have already made a number of important decisions and are already practised in letting the characters speak in their own unique way.

Speaking of decisions: What I really like is that Frey emphasises several times that although there are a lot of decisions to be made in the development process, they all remain open to discussion, revision and flexibility until the most brilliant dramaturgical solution is found.

How to create a fascinating setting

Frey recommends choosing a (crime) location as the backdrop for your murder that already harbours a conflict situation that readers have to position themselves to. In his example, he chooses a backwoods provincial town during the hunting season, which is always a destination for animal rights activists who want to protest against hunting. If you apply Frey’s trick to the scene of your crime, animosities between your characters are already smouldering beneath the surface.

This is how you give structure to your story

According to Frey, a „damn good“ crime thriller should tell the ancient, mythical story of how a warrior hunts down a monster and how she changes in the course of this momentous battle.

The story should unfold as a five-act play as follows:

- The main character accepts the (investigation) assignment,

- The main character is put to the greatest test, „dies“ and – in the key scene – is „reborn“ as a changed one,

- The main character is tested again and passes the test,

- In the climax of the story, the „showdown“, the main character convicts the perpetrator and brings him/her to justice.

- The final act recounts the effects of the events on the main characters.

Frey’s five-act model – which can be traced back to Gustav Freytag’s pyramidal drama construction (Freytag’s Technique of the Drama: An Exposition of Dramatic Composition and Art {Affiliate Link}), Campbell’s myth theory (The Hero with a Thousand Faces {Affiliate Link}) and Vogler’s screenplay dramaturgy (The Writer’s Journey {Affiliate Link}) – is sometimes out of the question for crime thrillers because they are often part of a series. It is simply implausible for a series heroine to constantly undergo new life-changing transformations. But Frey is well aware of this. He therefore recommends that the main characters in a series change their constellation and thus their attitude towards their fellow characters in the course of the plot, for example that enemies become friends and vice versa.

How to lay a solid foundation for high tension

Frey recommends creating an outline, a step by step description that briefly sketches each scene.

As the perpetrator and suspects are not idle behind the investigator’s back, Frey wisely recommends writing down both what happens „on“, i.e. in front of the detective’s eyes, and what happens „off“, i.e. in secret. Planning the architecture of the crime plot before you start writing it down allows you to optimise the plot structure with little effort. What’s more, you can use the outline to keep track of even the most intricate crime plots.

How to create gripping scenes

Just as the goals of the protagonist and antagonist conflict in the overall story arc, the individual scene is also designed as a conflict. Accordingly, it is elementary, my dear Watson, that you give your characters contradictory intentions and goals in every scene – in crime fiction this usually means: the investigating character wants to get to know something, the suspect does not want to reveal anything, Frey speaks of the principle of „insistence versus resistance“. As the conflict develops, the climax of the scene is a reversal in which one of the characters achieves their goal and the antagonism ends. The characters react to the reversal emotionally, leaving the scene changed. Good end lines create an arc to the next scene so that your thriller becomes a proverbial page-turner that entices you to read on.

How to seduce your audience into your story’s world

Frey names five techniques you can use to grab your audience’s attention and literally suck them into your fiction:

1. Raising burning questions about the course of the story,

2. Sympathy – which comes from feeling sorry for a character so that the audience becomes emotionally attached to them,

3. Empathy – by making your readers empathise with the feelings of your characters,

4. Identification – by giving your characters goals that your readers want them to achieve and …

5. … inner conflicts, contradictory desires, so that your audience puzzles over how your characters will decide in the course of the plot.

Frey mentions another indispensable „four pillars of crime fiction“: mystery, suspense, conflict and surprise. The ingredients mentioned are almost identical to the „four means of suspense“ that I described in my blog article on developing crime stories.

How to choose your narrative perspective

A first-person narrator only describes what she perceives, feels and thinks. By letting investigators tell the story themselves, you can achieve maximum identification and offer your audience the place of honour of being at the pulse of the action and always at the height of the investigation. However, this not only restricts the „field of vision“ – you can only report what the investigating character experiences or learns – but you also stylistically restrict yourself to the language of just one of your characters. If you narrate in the third person, this allows you to tell the story from multiple perspectives and also to vary stylistically, as the narrator on the one hand and as the narrating or thinking/feeling character(s) on the other.

This is how you write like Paganini

Once the characters‘ biographies and diaries have been drawn up, the outline is in place, the scenes are roughly outlined and the narrative perspective has been chosen, Frey favours writing the first draft prestissimo, preferably in one go and ludicrously fast – which, incidentally, is also what his screenwriting colleague William Goldman (Adventures in the Screen Trade {Affiliate Link}) recommends. Frey advises continuous writing anyway, so as not to unlearn your craft. To this end, he advises that you aim for around 1200 words a day – that’s five to six rough draft manuscript pages, which you then tighten down to around three pages in the revision process.

How to make your story shine

Speaking of the revision process: Frey does not fail to mention that the first version is never the last, that only the fine polish turns a rough diamond into a piece of jewellery.

Using his own work, he shows the process of polishing the text in four stages of development: how he tightens the structure, activates the language, optimises dialogue, finds suitable metaphors and accentuates sensual and revealing details. As you read, you look over the shoulder of the experienced crime writer as he works and are instructed by him en passant.

How to write in a captivating style

According to Frey, high-quality prose is clear, efficient, uses sensory details (and should appeal to different channels of perception, not just the sense of sight), uses metaphors sparingly and meaningfully, uses full verbs in the active voice and is emotional, making it clear how your characters perceive and feel. In order to maintain suspense, crime writers use not only sensual but also revealing details. By this he means the following: Readers – like the investigating characters – observe attentively, develop their own theories and draw their own conclusions. Accordingly, clues such as the style of dress, workplace, habits and behaviour of suspects reveal something about them and possibly also about the mysterious crime to be solved.

How to become a master in your field

You achieve mastery by avoiding the cardinal sin for authors: Not producing anything new. If you constantly develop something new and remain a persistent writer, you can’t help but continue to develop en passant. In a video interview Frey gets to the heart of the matter:

»Writing is a mental disorder«

James N. Frey

According to Frey, the best of his students are obsessives who can’t help but write.

How to make your manuscript irresistible to editors and agents

Finally, Frey gives tips on how to offer your finished crime thriller. He may have been helped by the fact that he went from house to house as an agent before becoming a writer. As soon as the author had finished the crime thriller manuscript, he was told to transform himself from a „creative genius“ into a „marketing freak“. You should find out which agents specialise in which types of books and write to them persistently. To do this, prepare a synopsis in which you compare your work with that of successful crime fiction authors, ideally those that the agent represents. It helps if your crime thriller could be the first in a series.

My verdict on Frey’s modern classic on crime writing: „Damn good“?

Frey’s book is definitely not a cultural-historical introduction to the genre of the crime novel, nor does it provide a systematic overview of all its varieties, nor does it venture any predictions about the latest trends in the crime genre. But that is not his intention at all.

Frey conveys practical, reliable methods for developing exciting crime plots – especially for the medium of the novel. Although Frey primarily addresses prose writers, his techniques are also suitable for you if you are a screenwriter, playwright, dramaturge or even a game designer. Journalists and bloggers can certainly also benefit from his handouts for good prose.

Frey is undoubtedly one of the „plotters“, i.e. those who carefully plan the plot and suspense structure before they start writing – in contrast to „pantsers“, who give free rein to their passion for writing and storytelling and tend to tighten, correct, regroup and polish retrospectively. If you follow Frey’s approach, you work efficiently and don’t just write at random. Frey also manages the balancing act of instructing beginners and advanced writers with equal expertise. In some respects, Frey is a little too exclusive for me personally, too convinced that (his) story structure is the only promising one. However, different views of the world and people require different narrative styles. After all, in art, if it deserves this title, there is no „right“ and „wrong“, only a form appropriate to its individual message. But since his book offers so much that is „damn good“, Frey can be forgiven for being brimming with self-confidence and convinced of his story structure.

By developing an exemplary crime plot from scratch, allowing us readers to watch and commenting on his working process, he provides valuable insights into the workshop of a crime writer.

Another advantage of Frey’s book is its clear, easy-to-understand, sometimes quite amusing, casual tone. I can therefore recommend Frey’s How to Write a Damn Good Mystery {Affiliate Link} to anyone who wants to learn how to commit, solve and narrate aesthetic crimes.

Sincerely yours,